An Imperfect Storm

By: Melissa Fralick | Categories: Tech History

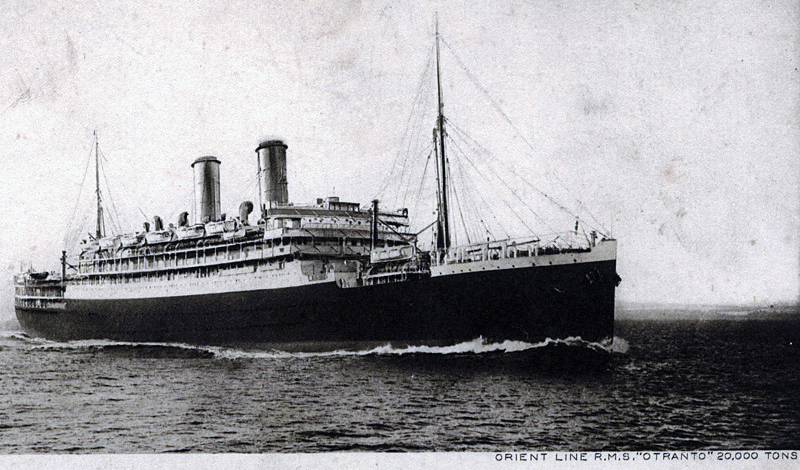

One hundred years ago, America suffered its worst troop ship disaster at sea during World War I: the sinking of the British troop carrier HMS Otranto.

Today, not many are familiar with the tragedy, which resulted in the loss of hundreds of lives, including more than 130 young men from Georgia. Even fewer are likely to know that their commanding officer, Samuel E. Levy, ME 1917, was a Georgia Tech alumnus.

To mark the centennial anniversary of this tragic accident, another Tech graduate, Levy’s grandson Chuck Freedman, IE 67, is working to ensure that the legacy of the Otranto is preserved.

Freedman is helping to plan a ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the incident with the installation of a memorial plaque at Ft. Screven on Tybee Island, Ga. It’s documented that at least 130 soldiers from Fort Screven’s Fifty-fourth Artillery Replacements were among those who perished in the Otranto disaster.

Freedman is also travelling to the Isle of Islay, off of Scotland, for a ceremony memorializing the sinking of the ship.

His grandfather was one of roughly 600 men aboard the Otranto who were able to survive through a harrowing escape, while around 470 more still aboard the ship perished. Though Levy was lucky to escape the ship alive, by all accounts his journey was agonizing from the start.

America officially entered WWI in 1917, and in July 1918, the HMS Otranto, an armed merchant cruiser, was sent to New York to ferry American soldiers across the Atlantic to join the fight. In the fall of 1918, urgent orders were sent for 580 enlisted men and four officers from Ft. Screven to report to Camp Merritt, N.J. for the journey to Europe.

2nd Lt. Samuel Elias Levy, of the Coastal Artillery Corps, was selected to command the troops. Levy’s Georgia Tech education made him a natural fit for the position.

“Lt. Levy was a near-perfect match for service with the Coastal Artillery Corps as Georgia Tech’s mission was to graduate men ‘able to grasp and solve mechanical problems,’” according to Many Were Held by the Sea, an historical account of the incident penned by R. Neil Scott. “Of particular interest was the emphasis Tech placed on developing leadership skills and character.”

The HMS Otranto departed on Sept. 25, 1918, leading the HX-50 Convoy across the ocean. There were more than 1,000 men aboard the ship, but that number dwindled almost immediately as hardship and tragedy struck the Otranto.

The ship set sail in the thick of hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean. Strong winds and heavy seas created mountainous waves, making the men on board violently sea sick. The stormy conditions were so severe that the men were confined below deck, where overturning buckets of vomit added to the already pungent odors of cow manure and chemical disinfectants from the Otranto’s previous journey.

Meanwhile, at least 100 men onboard were suffering from severe cases of the flu. The Otranto’s sick bay was so full that the main dining room was converted into a hospital. To make matters worse, doctors had a difficult time differentiating who had come down with the deadly flu virus and who was severely sea sick.

This was no ordinary flu, but a worldwide pandemic. In 1918, the Spanish Influenza killed millions of people —epidemiologists now believe up to 50 million worldwide. This powerful strain of influenza took down even young, healthy men like those aboard the HMS Otranto.

On Oct. 2, the first flu death occurred on the Otranto. From that point forward, at least one ship in the convoy experienced a death from influenza each day, and had to reduce speed to bury bodies at sea.

As the cross-Atlantic journey neared its end, weather conditions continued to worsen. On Oct. 6, hurricane-force winds, sleet and 40-60-foot waves made navigation difficult, and the ships in the convoy were pushed 20 miles north out of their formation.

As the cross-Atlantic journey neared its end, weather conditions continued to worsen. On Oct. 6, hurricane-force winds, sleet and 40-60-foot waves made navigation difficult, and the ships in the convoy were pushed 20 miles north out of their formation.

Spotting a rocky coastline to the east, an officer aboard the Otranto mistakenly believed it was the coast of Ireland and directed the ship to head north. Another ship in the convoy, the nearby HMS Kashmir, correctly determined the land ahead to be the western coast of Scotland, and steered south. This put the Otranto directly into the path of the Kashmir, a half mile away.

Moving with the force of the massive waves, the Kashmir struck the Otranto, tearing a deep gash into its side. Both ships were damaged, but the Kashmir was able to stay afloat and make it to Glasgow. Meanwhile, the Otranto’s boiler rooms were flooded, and the lifeboats were damaged in the crash.

Luckily, a British destroyer called the HMS Mounsey came to the Otranto’s aid.

The Mounsey’s captain, Lt. Francis W. Craven, bravely volunteered to take the American troops to safety.

Despite the severe conditions, Craven was able to skillfully maneuver his ship right alongside the Otranto several times to give the men on board a chance to jump to safety.

While jumping onto the Mounsey was the best bet for survival, it was also a lethal gamble. Many who attempted to jump fell into the sea, were crushed between the two ships, or landed on the deck of the Mounsey only to be swept away by the enormous waves.

Sadly, nearly 500 people were still aboard the sinking HMS Otranto as it drifted straight for the rocky cliffs of Scotland’s Isle of Islay. A wave dropped the ship on top of a reef, where it broke into pieces, sending the men onboard into the waves. All but about 20 of the men died after they were hurled into the boulders at the base of the cliffs.

The people of the sparsely populated Isle of Islay took on the grim task of sorting through the wreckage at their shore to retrieve and bury the bodies of those who died in the crash.

Freedman says he was moved by the story of how the people of Islay responded to the disaster.

“They were persistent about pulling every body over the shore and as best they could documenting who they were and marking the graves,” Freedman says. “They went and scavenged red, white and blue materials and made an American flag to fly over the remains.”

Levy was among the last to jump from the Otranto, and he landed safely on the Mounsey. The Mounsey was badly damaged from the rescue effort, leaking and weighed down with so many extra men. Craven steered slowly and carefully to keep the ship from capsizing as the men crowded together below deck in ice cold water for the remainder of the five-hour journey to Ireland.

The Mounsey arrived safely in Belfast, and Craven’s heroic effort saved 597 lives—including Levy’s.

Levy returned to Atlanta, where he went on to have a successful career as a realtor and the owner of Sam E. Levy Tire Company. He was active in civic affairs and the Jewish community. He remained “a rabid Georgia Tech supporter,” Freedman says, whose daughter attended the Georgia Tech School of Commerce, and whose son-in-law, grandson and great grandson went on to graduate from the Institute.

Despite his full life, he never forgot his experience aboard the Otranto.

Levy organized several reunions for the survivors, including one marking the 35th anniversary in Atlanta, which included a Georgia Tech football game. He organized the 50th reunion in Sylvania, Ga., where the majority of survivors lived.

As a Tech student, Freedman recalls his grandfather telling him the story of the HMS Otranto during several of his regular Friday night dinners at his grandparents’ house.

But he didn’t think too much about it until the 1980s, when a friend visiting Tybee Island spotted his grandfather’s name as part of a temporary exhibit dedicated to the Otranto at Ft. Screven. Later, his interest in the story was reignited when he was contacted by R. Neil Scott, a professor writing a book about the Otranto, who wanted to talk with him about his grandfather.

Scott, who passed away in 2012, shared his research materials with Freedman, giving him new details that helped him to better understand his grandfather’s story.

“A couple years ago I started thinking, we’re coming up on the centennial,” Freedman says. “Wouldn’t it be great to get together not only the families of the survivors, but the deceased? What better place to do that than down at Ft. Screven?”

Freedman began contacting local historians and the families of those who served on the Otranto. He got in touch with Charlie Calvert, a member of the American Legion, who was also working on a memorial marker for Ft. Screven and invited him to help plan the ceremony.

Through his research, Freedman has learned more about his grandparents, and he’s glad he’ll be able to leave this family history as a legacy for his own children. Freedman also believes that his grandfather would be glad to know that the families of the men who served aboard the ship would be together to mark the 100th anniversary of the Otranto’s sinking.

“With all the efforts that my grandfather went through to get the survivors together, I think it’s something that he would be glad I was doing,” Freedman says.

—Source: Many Were Held by the Sea: The Tragic Sinking of the HMS Otranto, by R. Neil Scott