Electric Dreams

By: Tony Rehagen, Photos by: Kaylinn Gilstrap | Categories: Alumni Interest

Ben Horst knew he was destined to be an engineer from an early age—much to his parents’ frustration. Horst was the child who took apart all of his toys, particularly anything with wheels and an electric motor.

“I would ruin them,” says Horst, ME 16. “I’d get a toy train with a motor as a Christmas present, and by the end of Christmas Day, it would be non-functional.”

Eventually, Horst’s folks just started buying him tools so he could assemble his piles of miscellaneous parts into things that actually worked. Again, his affinity for engines drew him to automobiles. He built his first go-kart out of natural-gas piping when he was still in high school. “I don’t know what it is about cars,” he says. “There’s something really rewarding about designing and building a car. It’s rewarding to build anything that works, but with a car you are able to get in it and have an adrenaline experience in the thing you built.”

Today, Horst’s gear-head tendencies are paying off in more than just adrenaline. In 2017, he and two fellow Tech grads—Josh Preissle, ME 16, and Kenny Adcox, ME 16—founded Eddy Motorworks in Atlanta. And what the trio does is something truly special. They take apart classic and specialty cars and put them back together again, replacing old gas-gulping engines with 100 percent electric powertrains. And in a warming world increasingly obsessed with hybrid and electric transportation, Horst and his company’s conversions have become the talk of the turnpike.

Horst’s quest for the cleaner classic car began at Tech back in 2013. He just didn’t know it at the time. He arrived as a mechanical engineering student at the Invention Studio, the student-run machine shop on the second floor of the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex, and started tinkering with the new toys. “Any tinkerer will tell you that as soon as you see a new tool, you start to think about what you can build,” he says. “I saw the water jet and laser cutters and started thinking about being able to build car-level components.”

In between two engineering internships at General Motors, Horst also joined Georgia Tech’s Solar Racing Team, where he got to see electric motor and battery technology up close. “It was so simple,” he says. “Especially compared to fixing a carburetor, which is this magical machine with emotions. I kept thinking ‘How cool would it be to build a go-cart with four independent electric motors?’”

During his last GM internship, Horst shared the concept for this ultimate go-cart with his roommate, whose father had connections at engine manufacturer Briggs and Stratton. Together, the interns came up with what they called the PH571—PH for Performance Hybrid and 571 for the apartment they had shared in Michigan.

The idea was to pair a 0.99-liter Briggs and Stratton V-twin with an HPEVS AC35 motor and a Smart Car battery, using the gasoline engine to pump out the baseline power while the electric motor provided the bursts of speed. By their calculations, the combo could achieve more than 100 horsepower and 90 miles per gallon or 50 miles of battery range for the ultra-light 1,300-pound tube frame.

The PH571 became Horst’s senior design project in 2015. He gathered a team of fellow student computer scientists and engineers, including Preissle, to make the high-performance hybrid vehicle a reality. The car was named best interdisciplinary project at the Tech Capstone Design Competition, and the win led to an invitation to and acceptance in the Institute’s CREATE-X Startup Launch program. Horst and Preissle received $20,000 in seed funding, free legal advice and entrepreneurial mentorship to start their own company. From this, Eddy Motorworks was born.

The company needed to jump-start business, so Horst and Preissle dropped their own cash to fund their first gas-to-electric sports car conversion project, a British MG MGB coupe they rebuilt in their garage in Scottdale, Ga. The project took months of their time and money, but they recouped much of their effort by eventually selling it to a local car aficionado.

Their first commission came through last autumn when Eddy Motorworks was hired to “electrify” a 1983 Mercedes-Benz 380SL. The goal was to create a car that was on par with the best electric vehicle on the market, the Tesla S, which has 200 to 250 miles of range, is fast-charging, and can go 0 to 60 miles per hour in just 3.5 seconds.

The challenge with such a conversion project, however, is all that power comes from batteries that take up a considerable amount of space. So how do you fit all of them within the sleek frame of a 1980s roadster and still make it look like a classic luxury car? “It’s like playing Tetris with batteries,” says Horst, who serves as Eddy Motorworks’ president.

The solution involved cramming several battery packs into the engine bay, the fuel tank area, and one underneath the trunk. Each pack is outfitted with a state-of-the-science carbon-fiber enclosure and waterproof connectors. The result is an ongoing $70,000 redesign that should, when completed, run with just about any electric car on the road.

During this time, a second commission came in the shop doors—no less than a sleek, stainless-steel-paneled DeLorean DMC-12 straight out of Back to the Future movie fame. Luckily, the order didn’t stipulate the conversion to generate 1.21 gigawatts of power or the ability to travel through time.

Yet for Horst, every build is a sort of time machine back to the kid in him who just likes to tinker. “I’m just building with intuition,” he says. “It’s fun and it’s something I’ve always wanted to do.”

Converting The Classics

Electrifying a traditional gas-engine sports car and having it perform up to the standards of, say, a Tesla, is no mean feat. It takes a great deal of careful work—and a considerable sum of money—to strip down a car to its bare bones and build it back up again with a completely electric-powered system. Eddy Motorworks President Ben Horst, ME 16, shares a sneak peek inside the process.

Some Disassembly Required

Some Disassembly Required

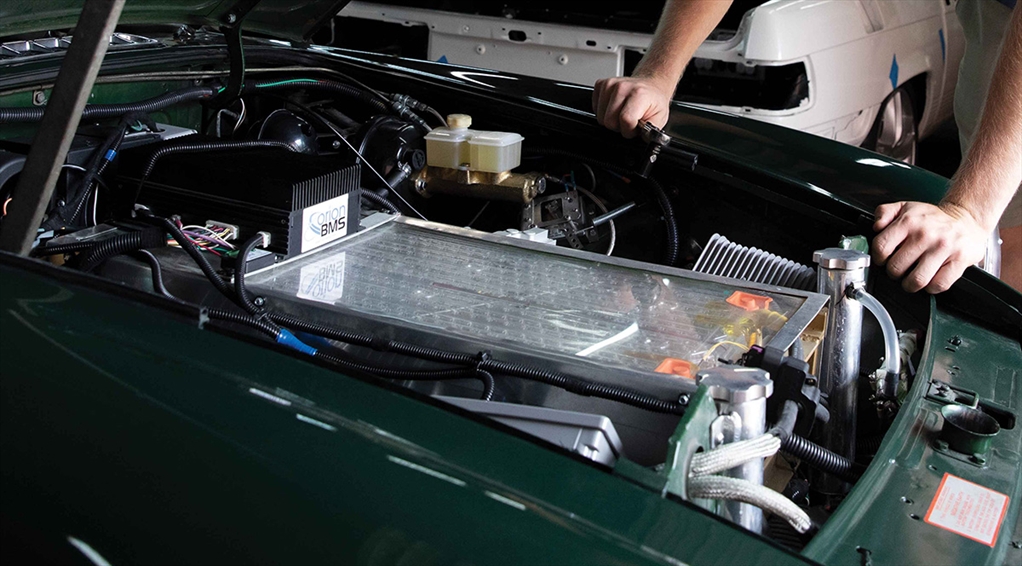

“It all starts with the tear down,” Horst says. “After we’ve decided on the build, we get to taking apart the vehicle (here a 1983 Mercedes-Benz 380SL). We remove the engine, transmission, differential, wiring harness and anything else that won’t remain in the conversion. When we’re done with disassembly, the car will be down to its body and frame, ready for the design work to begin.”

Designing The Build

Designing The Build

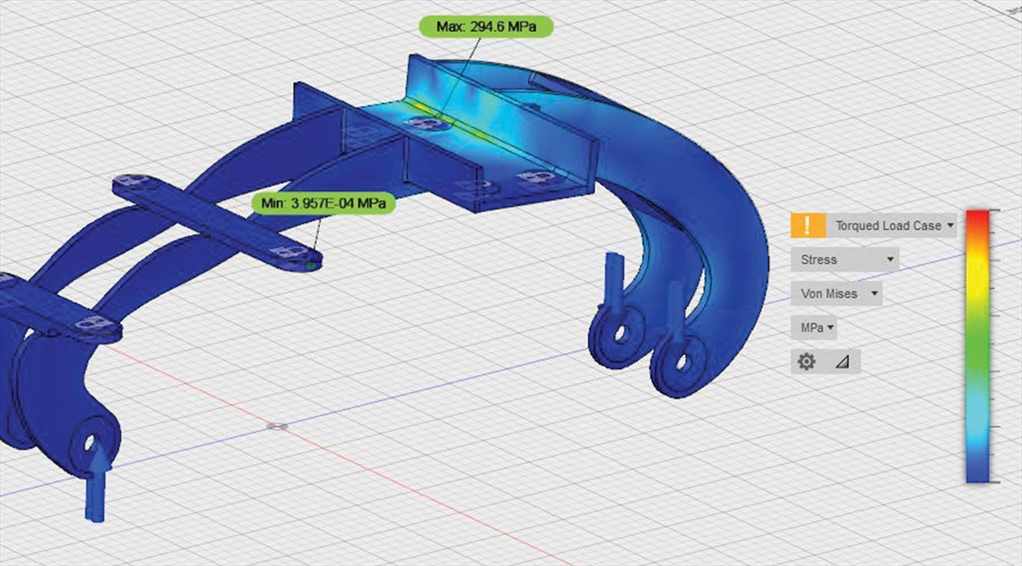

“With the car stripped down, we begin by taking 3D imaging scans to bring the geometry of the engine bay, underbody, trunk and fuel tank area into the computer,” Horst says. “From there, we get to work designing mounting structures for the batteries, motor, charger and other major components. For the very important parts, like the motor and batteries, we perform detailed structural simulations to identify areas of high stress, employing the same software tools that major automotive companies use to ensure that parts are strong and safe. These computer models also allow us to optimize weight.”

Fabrication and Welding

Fabrication and Welding

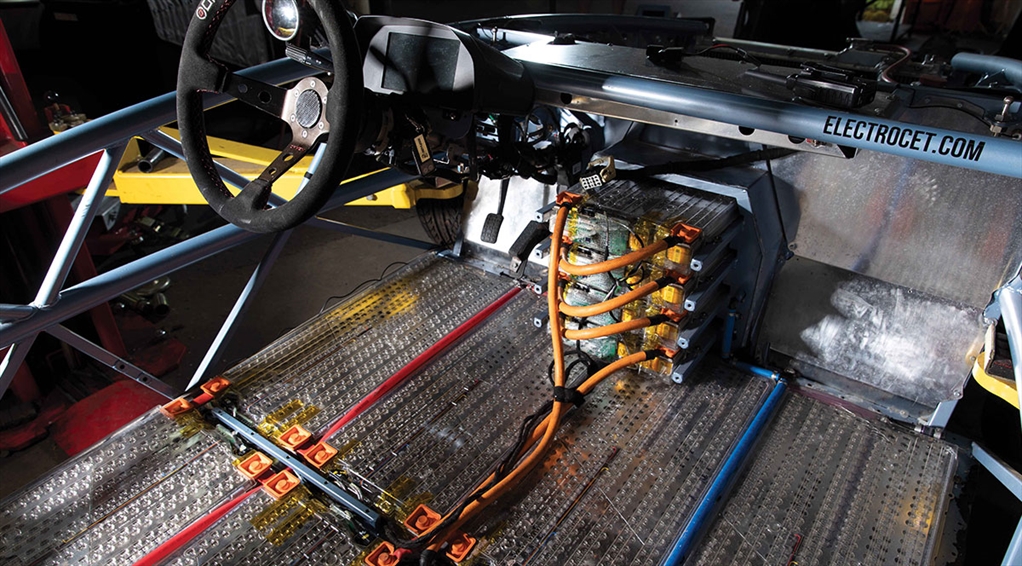

“With the design complete, the work now moves back into the shop where our extensive fabrication experience comes into play,” Horst says. “The batteries are mounted in the vehicles with strong, aircraft-grade chromoly steel tubes, precisely cut and expertly TIG-welded into a stiff structure.”

Batteries Included

Batteries Included

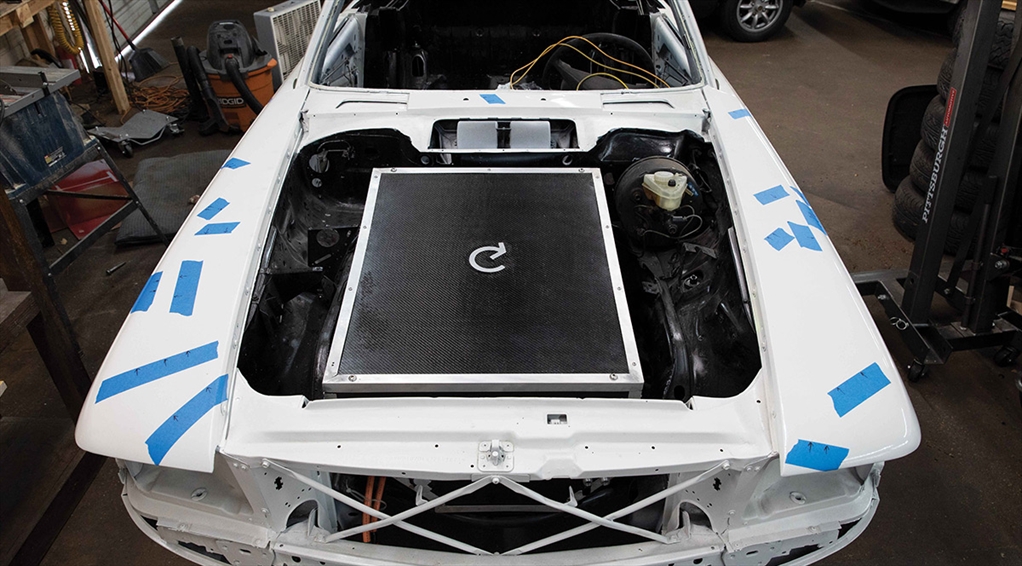

“Depending on the vehicle, there may be a single battery pack or multiple packs placed throughout the car to optimize weight distribution and maximize cargo space,” Horst says. “The faceplate of the battery houses a supersafe, finger-proof, high-voltage connector that allows for quick, safe servicing. With the packs all connected, the final step before installation into the vehicle is enclosing and sealing the batteries from the elements. With sealing complete, we carefully install the assembled pack into the vehicle utilizing vibration-isolating mounts and high-grade bolts.”

A Perfect Fit

A Perfect Fit

“Each car is its own puzzle,” Horst says. “Sometime you have to get creative to fit all the parts into place, whether it’s on a classic car like the Mercedes or a race chassis (pictured here). Sometimes that even involves grinding sheet metal so that everything lines up perfectly and is safe and secure.”

Just Drive

Just Drive

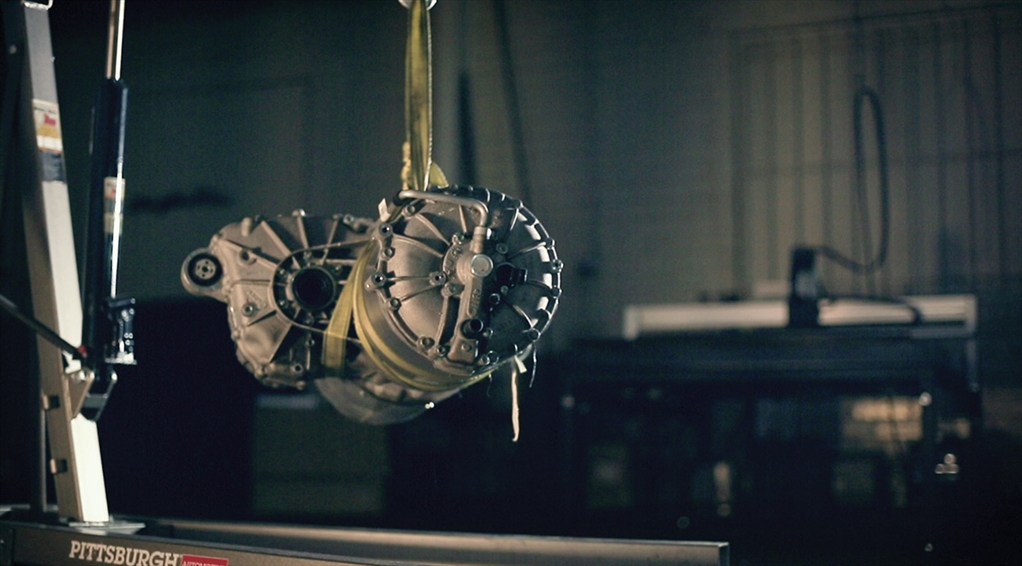

“Mounting the drive unit assembly— the motor, inverter, transmission and differential—is a similar process to the battery integration,” Horst says. “We take our computer-validated designs and send them to our CNC plasma machine, which cuts the individual parts out of sheet steel. We then carefully TIG weld those parts together into a full motor mounting structure. After a few coats of paint for rust protection, we bolt the motor into the vehicle. We use custom-built, highstrength CV axles to interface a Tesla drive unit to the wheel hubs. While we’re there, we upgrade brakes, bushings and bearings and install a new electric parking brake system.”

Making the Connections

Making the Connections

“One of the most challenging, yet extremely important aspects of building a custom electric vehicle is designing a safe, high-voltage distribution and connection system,” Horst says. “We use a network of high-current contactors, relays and sensors to ensure that high-voltage only leaves the battery pack when it is completely safe to do so. Our battery management system constantly monitors the state of health of the battery and detects ground faults, shorts or parasitic losses that could lead to failure.”

Mission Control

Mission Control

“When the classic cars we convert were originally built, their electrical systems were completely analog,” Horst says. “In modern vehicles, with an ever-growing number of sensors, actuators, lights and buttons, this wiring harness would quickly become enormous. We have developed a number of proprietary microcontroller modules that we install to sense buttons and switches and actuate lights, locks and windows all around the car. This greatly reduces the number of wires we have to run.”

Digital Displays

Digital Displays

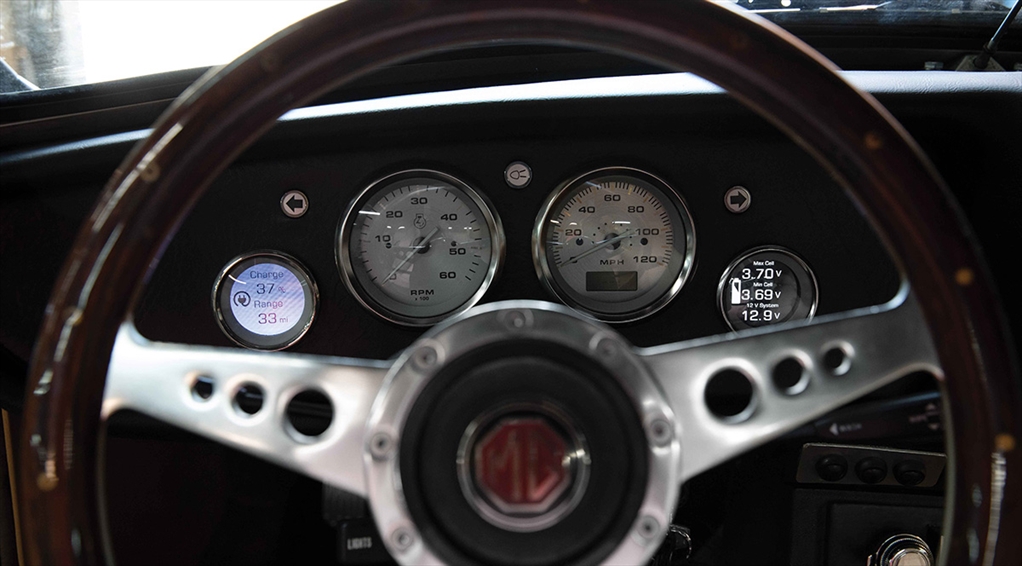

“Thanks to these interconnected vehicle control systems, we can install modern LCD displays with all the important information about your vehicle and its powertrain or we can build a custom, retro-style gauge cluster with analog-style dials and gauges. Either way, we take the time to build bezels and mounts that seamlessly integrate the user interfaces with the styling of the vehicle.”

Back to the Future

Back to the Future

“We haven’t started working on this one yet,” Horst says of the DeLorean that’s waiting its turn in his shop. “But we’re excited about the challenges and possibilities this rare vehicle presents.”