Tech's Brilliant Sculptor

By: Melissa Fralick | Categories: Tech History

Next time you find yourself strolling around campus or through downtown Atlanta, pay attention to the details of the handsome buildings around you. There’s a chance that the stained-glass window or architectural sculpture that catches your eye just might be the work of a Georgia Tech artist.

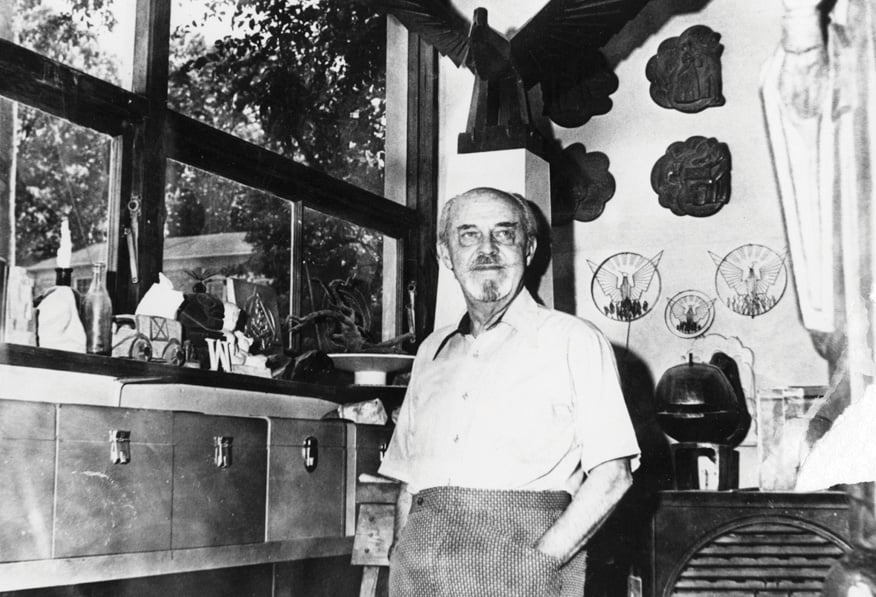

Julian Hoke Harris, Arch 28, was a long-time Georgia Tech architecture professor and a prominent sculptor who worked from his studio on Fifth Street to create art, medallions and sculptures that have adorned more than 50 buildings around the Southeast.

Some of Harris’ early works can still be seen on campus today. He designed the monumental stained-glass window (see photo on page 104) in Brittain Dining Hall’s southern wing, which features allegorical figures of the disciplines taught at the Institute when the building opened in 1928. He also created the 10 limestone busts (page 103) adorning the building’s columns, which represent great engineers and scientists throughout history.

In the 1930s, he designed the bronze gate (page 105) of the now-demolished Naval Armory, which was cast on campus by “Uncle Billy” Van Houten, one of Georgia Tech’s first instructors and the foreman of the Georgia Tech foundry. Today, the gate is housed inside the Stephen C. Hall Building.

Harris’s free-standing and relief-sculptures can be found well beyond campus on numerous Art Deco-era public buildings, including the Georgia Department of Agriculture Building (Animal Husbandry and Farming, page 105) and Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown Atlanta and the Georgia State Prison near Reidsville, Ga. He also made more than twenty commemorative medallions, including the official inauguration medal for President Jimmy Carter, Cls 46, Hon PhD 79.

Harris’s free-standing and relief-sculptures can be found well beyond campus on numerous Art Deco-era public buildings, including the Georgia Department of Agriculture Building (Animal Husbandry and Farming, page 105) and Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown Atlanta and the Georgia State Prison near Reidsville, Ga. He also made more than twenty commemorative medallions, including the official inauguration medal for President Jimmy Carter, Cls 46, Hon PhD 79.

Credited with pioneering the use of the of the jet flame in sculpting, he perfected a technique that was used to complete the Confederate Memorial Carving on Stone Mountain. His sculpture of a Madonna was the first sculpture completed entirely in that method without the use of a chisel.

Harris’ work was a unique blend of sculpture and architecture. He was awarded the prestigious Fine Arts Medal from the American Institute of Architects, which “honors an architect who found in sculpture the means by which he could recapture that close interweaving of the two arts which was known to some great epochs of the past and which raised the two to heights unattainable by either art alone.”

In a 1971 interview with the Georgia Tech Alumnus magazine, he said that his architectural education had a profound influence on his art.

“Had I known I would be a sculptor, I wouldn’t have gone to Tech—but it’s turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me,” Harris said. “My knowledge of architecture has enabled me to collaborate with 18 or 19 architecture firms on artwork for 50 buildings, to do sculptures that are in character and scale with the design of the building. And the principles of design in architecture and in art are the same.”

Though he isn’t a household name, Harris’ influence has been monumental to the art and architecture of Georgia Tech, Atlanta and the state of Georgia. You just have to know where to look.

The striking stained-glass window in Brittain Dining Hall was designed by Julian Hoke Harris. The building opened in 1928.

The striking stained-glass window in Brittain Dining Hall was designed by Julian Hoke Harris. The building opened in 1928.