60 Years. Celebrating Our Past, Continuing Our Legacy.

By: Kelley Freund | Categories: Tech History

But of course, that’s not the whole story. When statues commemorating these men were unveiled on campus in 2019, the men were on hand to speak, telling stories no one in the Georgia Tech community had heard before—stories of social isolation, discrimination, and how they were actually guarded by plainclothes policemen around campus.

The narrative surrounding how desegregation occurred at Georgia Tech was told from the viewpoint of the administration, says Jeanne Kerney, CE 84, who serves as president of the Georgia Tech Black Alumni Organization (GTBAO). “No one ever asked the students how they felt or what actually happened to them.”

To honor the 60th anniversary of Black students matriculating at the Institute, the GTBAO is telling those stories. The organization has planned a yearlong commemoration entitled “60 years. Celebrating Our Past, Continuing Our Legacy,” and during the coming months, the community will remember those challenges early Black students overcame, and celebrate their successes and the contributions they have made to Georgia Tech.

The GTBAO plans to host a series of podcasts with the school’s early Black alumni, as well as early Black faculty and staff. The organization is also collaborating with the Office of Development to create a digital yearbook. The yearbook will allow Black graduates to connect with fellow classmates or other alumni who live in their area. And through organizing the yearbook, the GTBAO hopes to gather the names of those who served as officers in early Black campus organizations, as those have never been officially recorded.

“The celebration is about the fact that we’ve made it through,” says Kerney. “But it’s also about capturing the historical narrative of the Black experience at Georgia Tech, as told by students, faculty, and staff. What did we go through, how did we prosper? Because our story is different.”

Here, a few of those early alumni discuss their time at Georgia Tech and what the Institute means to them today.

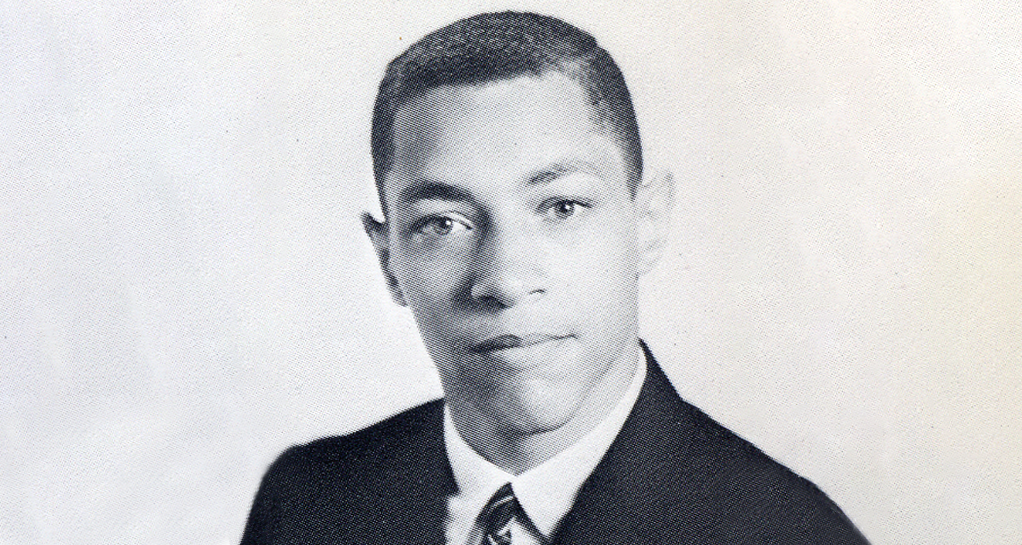

Ronald Yancey, EE 65

First Black Graduate at Tech

Dean James Dull gave me a tour of the campus a week before school started. He said, “You will be protected by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. They’ll be attending classes. You won’t know them, but they’ll be with you.”

I met hostility. Fortunately, having been in demonstrations and sit-ins in downtown Atlanta, I had some skills in identifying when a crowd was becoming dangerous. I knew how to watch my back, but I never felt like I was alone on campus because of my faith. But to give you some perspective, the whole time I was at Tech, I only saw a Black student twice on campus.

There were a couple incidents that I look back on now that I feel good about. I remember in 11th grade, I read an op-ed in the Atlanta Journal that said it would be 20 years before an African-American would graduate from Georgia Tech. That infuriated me. I said we’ve got to do something about that.

I also remember an incident when I was 10 years old riding the bus with my mother. A sign on the bus said “White passengers seat from the front. Colored passengers seat from the rear.” I sat down in front of my mother and a white gentleman got on the bus and went straight to me and said, “Get out of that seat. There are seats in the back.” I went to sit next to my mother and I looked at her face. For the first time, I saw on her face a mixture of anger, hurt, and rejection. But I didn’t see fear. From that point on, that became personal to me.

When I graduated, I said, “This is for you, mom.”

*Yancey’s story is collected from a 2019 Diversity Symposium panel discussion.

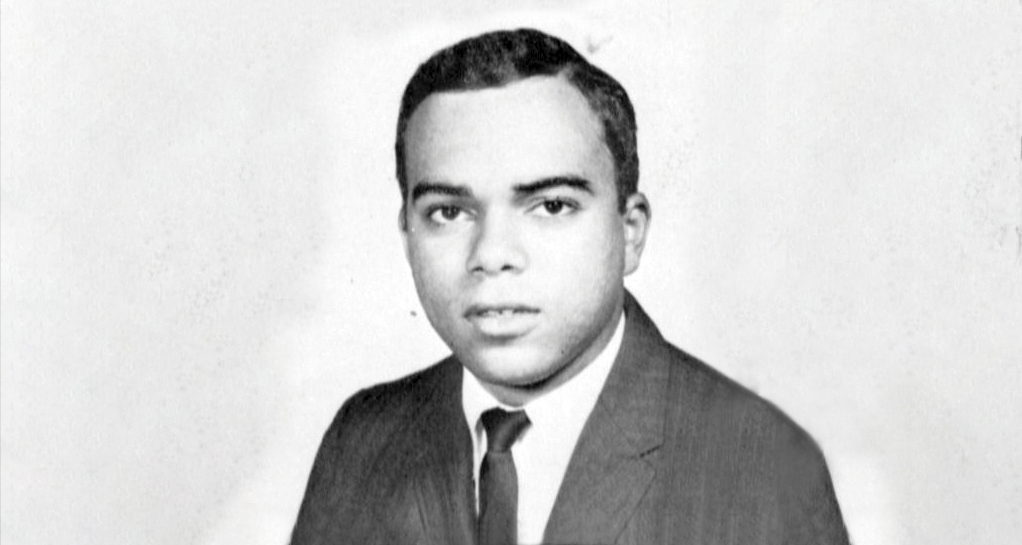

Charles McKinney, CE 69

One of the First Black Students at Tech

I have lighter skin, and that’s known as “flying under the radar.” I have been identified as the Black guy, but I have also been known as an East Indian. Whenever I was identified as East Indian, it was because I did something really cool. When I did something bad, I was the Black guy.

One year, I turned in cards for class registration, and within 45 minutes I had a note from a social studies professor in my mailbox, asking me to come see him. When I went into his office, he had a large Confederate flag hanging up. He told me I should drop his class, and if I didn’t, then I wouldn’t pass.

I did A work, but got Bs on my coursework and a C for that class. A quarter later I looked up my file, and my C had been changed to a D. All right, if that’s the environment I’m working in, I’ll just have to take more classes. Let me tell you, I got myself an education.

I am a Georgia Tech graduate. You can give me bad grades. But one thing you can’t take away from me is my knowledge. I left with a deep understanding of civil engineering, its supporting sciences, and personal self-confidence. Georgia Tech is a fantastic place and makes good people. Why did I go to Georgia Tech? Because I want to be the best. Why did I send my kids to Georgia Tech? Because I wanted them to be the best.

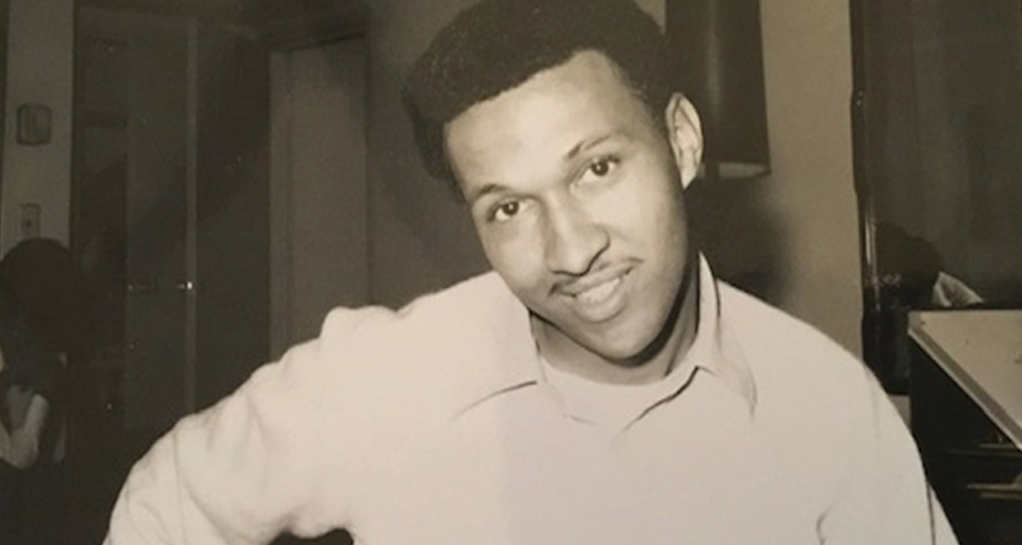

Haywood Solomon, IM 70

First President of the Georgia Tech Afro-American Association

My childhood neighborhood in southwest Atlanta was a Black, self-sufficient community with doctors, lawyers, restaurants, and theaters. If we left that community, we faced discrimination, so it wasn’t something my family did often. But as the country became more integrated, I knew that someday I would need to be able to function in a multicultural, multiracial environment. So I came to Georgia Tech.

There were just five other Black students in my freshman class, at an institution of over 7,000. At football games, students stood when the band played “Dixie” (but my friends and I stayed seated), it was difficult to find professors who offered support, and there were no organizations for Black students to turn to for resources.

My sophomore year, I helped found the Georgia Tech Afro-American Association (GTAAA) and served as the organization’s first president. The GTAAA created study groups for Black students, worked with administrators to set up the Black House, where students could socialize, and organized a Black History Week. I began to feel more a part of the school in my later years at Tech, when I became a teaching assistant and served on the Judiciary Council of the Student Government Association.

All the jobs I’ve had over the years have required me to interact with people of different races and socioeconomic status. And that’s what I saw at Tech. My experience at the school showed me how to function in a multicultural society. Without it, I would have had a more difficult time making that transition to the business world.

Evelynn Hammonds, EE 76

Teaches African-American studies, History of medicine, Science and Race at Harvard University

The atmosphere on Tech's campus was always tense.

You felt like anything could set off some racial issue. But mostly, the white students and Black students just stayed apart from each other. We were in a separate world.

Anytime we had to work collaboratively, white students made it clear they did not want to work with us. And I faced double discrimination being a Black woman. I remember labs where the guys would hand me a notebook and say, “Evelynn, take notes. You can’t touch the equipment. You have to take notes.” When I would complain to the lab director or professor, they would ignore me, or say, “That’s just how it is. This is what you have to put up with.” They refused to intervene on my behalf.

My experience was extremely hard. I wanted to quit many times. But my mom kept me going. She said if I didn’t think I could do the work or the work wasn’t interesting to me, then I could quit. But I couldn’t quit just because people didn’t want me to be there.

Today, there’s more diversity at Georgia Tech than I could’ve ever imagined when I was a student, and the atmosphere is much more conducive to producing the nation’s top engineers. That’s the ultimate goal. We want students to feel valued and safe in a place where they can just concentrate on being innovative and creative engineers and use their talent to change the world for the better.

Tawana (Derricotte) Miller, IM 76

First Black woman to enter Georgia Tech as a freshman and graduate with a bachelor's in the four-year program at Tech.

When I entered Tech, the mentality was, “Look to your left. Now look to your right. Only one of you is going to graduate.” I had no idea I was going to be the one to make it.

Professors mispronounced my name and ignored me, white students used the N-word, and once, some of them hung pictures of monkeys on Black students’ doors. Many of the Black athletes majored in industrial management, so I had support from them, and when I joined the Flag Corps, that also served as a support group. But for the most part, I didn’t have time to think about race. I was on a mission: Get in, get out, get a job. Tech teaches you how to work hard, if nothing else. Not only did I graduate, but I graduated early. I realized my Georgia Tech education opened so many doors for my career that today I bleed gold.

Three of my four children have a Tech degree, as do my brother and nieces and nephews, and I have highschool-age grandchildren I hope will enroll. So we are now seeing second- and third-generation Black students go to Tech. If we’re talking about “continuing our legacy” this year, I want that for my family legacy. I used to be jealous, hearing other students talk about how their grandfather attended the school. But time has passed, and now we can participate in that conversation.

Continuing Our Legacy

What do the next 60 years hold? Kerney hopes they will bring more Black students to Georgia Tech.

“Tech is currently 5 percent African-American, and has been that way for a long time,” she points out. “We’re not losing ground, but we’re not really gaining ground, either. Georgia is 30 percent African-American. Surely we can find a few more people who want to come here.”

This past year, the GTBAO was able to provide a student with a multi-year scholarship for the first time. In honor of the anniversary, the organization is kicking off an endowment campaign in order to provide more multi-year scholarships and bring more Black students to Tech.

But what happens once they get here? Kerney thinks the Institute has done a wonderful job creating academic opportunities for minority students—Georgia Tech is consistently rated among the top universities in the nation for the graduation of underrepresented minorities in engineering, physical sciences, and architecture and planning. The Institute’s new Strategic Plan also includes actions focused on further expanding access to underrepresented minorities, women, and low-income students. The Institute’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Office focuses on recruiting and retaining a diverse team of students, faculty, and staff.

“But that student-life aspect is also very important,” Kerney says. “From a culture standpoint and the enjoyment of life on campus, I think that’s where we can improve and help students graduate with more positive feelings about Tech.”

Which is why the GTBAO is asking the administration to consider building a Black cultural center on campus. It would be a place for students to hang out, where Black campus organizations can keep their records, and where students can learn and celebrate the achievements of their culture.

That last part is a very important point for Kerney, who gets a call about once a month from families wanting to talk with her about sending their child to Tech. “Often the student will say they think Tech will be too hard. But what makes people think that Tech is not a place where Black people can prosper? Because I can show you too many who have [prospered]. We have to get that story out.”

Visit www.gtbao.gtalumni.org for information on how to support to BAO Scholarship Campaign.